Wednesday, March 31, 2021

RRR presents... MEMOIRS OF A KARATE FIGHTER by Ralph Robb - GUEST POST + EXCERPT!

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

RRR presents... THE TICKLEMORE TATTLER by Liz Davies - SPOTLIGHT!

Monday, March 29, 2021

RRR presents... AFTER THE ONE by Cass Lester - REVIEW!

Sunday, March 28, 2021

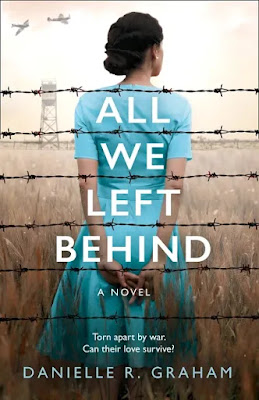

What's the BUZZ?: All We Left Behind by Danielle R. Graham - REVIEW!

Saturday, March 27, 2021

I'll tell you a tale of... VAMPIRATES: Demons of the Ocean by Justin Somper - REVIEW!

RRR presents... PLUTO'S IN URANUS by Patrick Haylock - EXCERPT + GIVEAWAY!

Thursday, March 25, 2021

RRR presents... NOTHING MAN by R.J. Gould - SPOTLIGHT!

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

RRR presents... SUMMER SIN by K.S. Marsden - COVER REVEAL!

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

TCBR AWARENESS TOUR: A Most Clever Girl by Jasmine A. Stirling - REVIEW + GUEST POST + GIVEAWAY!

Why Jane Austen? What could a witty woman who lived more than 200 years ago and wrote books for adults about finding love have to offer today’s young women and girls?

The answer is, plenty. So many things, in fact, that narrowing them down for this article was a daunting task. Read on to learn why Jane Austen is an awesome role model for girls!

1/ Jane Austen was a rebel with a dark sense of humor

Jane Austen was far from being the prim, prudish, “dear Aunt Jane” depicted by her brother Henry and her nephew Edward in their biographies of the author after her death. In fact, from age 11 or earlier, Austen was an unabashed rebel on paper (and sometimes in real life, too). Although her father was a clergyman, and educated girls in the Regency era were expected to be demure and submissive, Jane entertained herself and her family by gleefully writing (and reading aloud) a torrent of downright shocking, even amoral stories featuring adultery, drunkeness, suicide, and murder. Her chosen art form at this age was comedic parody—the darker, the better.

After she grew up, Jane’s rebellious streak and sense of humor persisted. When the librarian to the future king of England, James Stanier Clarke, suggested that she write a serious historical romance, Austen flatly declined. She responded that although writing such a work might be profitable or popular, she “could not sit seriously down to write a serious Romance under any other motive than to save my Life.”

After she grew up, this rebellious bent found its way into Jane’s characters as well. In Pride and Prejudice, Lizzy Bennet tells her aristocratic antagonist Lady Catherine de Bourgh, “I am only resolved to act in that manner which will, in my own opinion, constitute my happiness, without reference to you, or to any person so wholly unconnected with me.”

Looking for examples of rebel girls and women who felt empowered to think, do and say exactly what they wanted to? Look no further than Jane Austen! Your girls just might find her wild adolescent writings and bold quips as a grown-up to be exactly what they didn’t expect.

2/ Jane Austen bucked traditional gender roles, focusing more on what made her happy than on fitting in

In Jane Austen’s day, girls from educated families were groomed to become nothing more than fashionable wives. If a respectable lady had an interest in books and learning, she hid it. Girls were expected to be quiet and dainty and demure.

Jane Austen bucked these conventions. One of her favorite pastimes was rolling down the hill near her house with her brothers. Although she had little formal education (because she was a girl), she devoured as many books as she could get her hands on in her father’s library. Jane was also mischievous; she loved to play practical jokes on her brothers, and even her clergyman father. She went as far as creating two farcical entries in her father’s official record of local marriages, both claiming that she had gotten married (to different men).

Then at age 26, although she knew it would likely be her last chance to marry and secure her financial future, Jane Austen accepted, and then promptly rejected, a marriage proposal from a wealthy family friend, because she didn’t love the man, and found him ill-mannered and quick-tempered. Instead, Jane chose to be a spinster and a writer—the most unpopular and unfashionable choices she could have made in the eyes of the society in which she lived.

Jane’s refusal of this proposal meant that she would remain dependent on the charity of her brothers for the rest of her life. But Jane didn’t take this fate lying down. Instead, she wrote several novels that she hoped would (and most certainly did) help make her more financially independent. She also fought to gain back the rights to a novel that one publisher had purchased, but never published. All of these moves were considered shockingly unladylike in the eyes of the culture in which Jane Austen lived. Indeed, by taking up the pen at all, Jane Austen was venturing into a male-dominated realm. Men held the pen, and—with a few exceptions—only men published.

All of us should be so wise. Jane’s example teaches every girl to tune into her deepest self and make choices that will make her happy. If that means challenging gender norms, choosing an unpopular and unprofitable career, or saying no to a partner despite social pressure to marry, so be it.

As a teen, I was painfully concerned with what my peer group thought of me. I wish I had known what Jane knew at that age. Take it from Jane, girls—focus more on what makes you happy than on fitting in.

3/ Jane Austen’s heroines challenged the prevailing notion of the ideal woman as decorative, passive, emotional, and morally perfect.

When introducing Austen’s novels to young women, it is helpful to point out that the ideal Regency lady was about as different from Lizzie Bennett as you can imagine. As one author wrote of the Regency ideal:

“The feminine ideal . . . may best be defined as an interesting compound of moral perfection and intellectual deficiency . . . She was required to be before all things a “womanly woman” meek, timid, trustful, clinging, yielding, unselfish, helpless and dependent, robust in neither body nor mind, but rather “fine by defect and amiably weak.””

In addition to being morally perfect and intellectually deficient, the ideal Regency bride was very young, and came with a large fortune—which her husband would take possession of immediately after the wedding.

Seen in this light, Lizzy Bennet is not only an incredibly charming, lovable leading lady filled with quirks and flaws; she is downright subversive. In fact, in one way or another, all of Austen’s heroines challenge gender norms or fall far short of the Regency ideal. Yet are all rewarded handsomely at the end—with love and riches. Lizzy is cheeky and opinionated, Emma is insensitive and meddlesome. Elinor and Marianne are frightfully poor, while Fanny is both poor and low-born. Catherine is obsessed with novels, and Anne Eliot is old and no longer pretty. Most of Austen’s heroines (Emma being an exception) are intellectual and well-read.

Furthermore, it is taken absolutely for granted by Austen that each of her heroines is, or can become, able to make her own life decisions—without any reference to men, her parents, or her social betters. This alone is a radical assumption, coming from a culture in which gender, family honor, and class dictated nearly everything a woman was permitted to say, do, and think.

But Austen didn’t stop there. She also used humor to challenge notions of ideal femininity. In Mansfield Park, Lady Bertram is so passive that she is unable to rise from the sofa, let alone form her own thoughts. Entertaining, frivolous characters like Lydia Bennet and Mary Crawford are viciously satirized. Traditional Georgian accomplishments such as “netting a purse” are ridiculed. Furthermore, Austen’s most desirable male suitors have no interest in the ideal Regency woman. Mr. Darcy, for example, requires that his mate possess “the improvement of her mind by extensive reading.”

In fact, I am hard pressed to point to heroines in today’s novels, films and TV shows that shine quite as brightly or depict women quite as realistically as Jane Austen’s did more than 200 years ago.

By raising up complicated, unique, bright, obstinate, and flawed women, then showing us their struggles and journeys of transformation, and finally rewarding them with love and happiness, Jane Austen obliterated unrealistic (and frankly, disturbing) notions of perfect, monolithic femininity, forever upending the way the world viewed women.

I distinctly remember my first experiences reading Austen as a young woman. It was the first time I had felt such a deep kinship with any heroine in any book—and I was an avid bookworm. Austen’s leading ladies felt like me and the young women I knew. If that’s not something worth sharing with today’s girls, I don’t know what is!

4/ Jane Austen’s heroines helped readers experience first-hand the shockingly precarious and brutally inhumane status of women in Regency England.

During the Regency period, marriage required a woman to give up everything to her husband—her money, her freedom, her body, and her legal existence. Husbands were legally permitted to beat their wives, rape them, imprison them, and take their children away without their consent.

Divorce in the Regency era could only be achieved by a private act of Parliament, and was exceedingly rare. Lower classes could sell their wives in the marketplace, which functioned as a form of divorce. The woman was led to market with a halter tied around her neck and sold to the highest bidder.

The laws of primogeniture and entailed property dictated that, upon his death, the bulk of a man’s inheritance typically be handed down to his eldest son or closest living male relative. If a woman inherited anything after her husband died, it was arranged at the time of the marriage and based on the assets she brought to the union. Often she got little or nothing at all.

Opting out of marriage was not a viable option for most women. Because most people believed that females were vastly intellectually inferior to males, there were no universities for women, and nearly all professions were reserved exclusively for men. A spinster often faced a life of poverty, ridicule, and dependence on the charity of her male relatives.

As a result, for Austen, “a story about love and marriage wasn’t ever a light and frothy confection.” Hidden in all that effervescent prose are subtle but seething critiques of Regency society, laws, and gender norms. Austen used romantic comedy to expose the incredibly high stakes of the marriage game for women who had no other options. She helped readers see the precariousness, anxiety and vulnerability of real women—showing the brutality of their situation more poignantly, entertainingly, and intimately than any political treatise could have achieved.

In Sense and Sensibility, we feel the injustice of inheritance laws when Henry Dashwood dies and his wife and children are forced to leave their home and live at the mercy of the heir, Mrs. Dashwood’s stepson, John. John chooses to give them little help, and overnight, Mrs. Dashwood goes from living in splendor to barely scraping by.

In Pride and Prejudice, the key context for the story is that the Bennet family home, Longborne, is entailed to the insufferable Mr. Collins. If his daughters do not marry before their father dies, they will be left to depend on the charity of their male relatives (a situation Austen knew well, as it was hers after her father died).

Although Austen’s heroines find both love and riches, unhappy and loveless marriages far outnumber happy ones in her novels. Wickham is bribed into marrying Lydia; she will have to endure a lifetime of his womanizing ways. Willoughby rejects Marianne, opting for Miss Grey’s £50,000. Charlotte Lucas, twenty-seven years old and superior in character, temperament, and intellect, to the pompous and revolting Mr. Collins, accepts his offer of marriage because "it was the only honourable provision for well-educated young women of small fortune,” thereby relieving her brothers of the burden of providing for her as an old maid. In fact, Charlotte “felt all the good luck of it.”

In these and many other examples, the reality of women’s narrow options, their shocking lack of personal freedom, and their extreme financial vulnerability ring loud and clear. For the first time in history, Austen’s novels humanized and personalized women’s issues in a revolutionary way, adding fuel to the fire for radical new ideas that were just beginning to circulate about women’s rights, education, and opportunities.

When I speak to girls about Jane Austen, they are often shocked to learn how limited the lives of women were in Regency England, which opens up rich conversations about gender roles and discrimination today. That Austen’s novels exposed these realities in intimate and personal ways makes her all the more compelling as a role model for girls.

5/ Jane Austen championed the radical notion of the ideal marriage as a match between two rational and emotional equals.

While the bleak fates of some of Austen’s female characters illustrate the limited options facing women in the Regency era, happy endings await her heroines. These happy endings also challenged traditional notions of marriage, which typically looked very unlike that of Lizzie Bennet and Mr. Darcy.

A middle or upper class Regency marriage was often a male-dominated exchange, dictated by two families coming together to consolidate their fortunes. When she married, a woman passed from the control of her father to that of her husband. She might have the opportunity to reject a suitor, or choose from a number of suitors; or she might be a passive participant in this exchange, depending on her circumstances and family culture. In either case, her submissiveness after the wedding was considered crucial to its success. Austen rejected this model of marriage as ideal in her novels and in her life, writing to her niece that “nothing can be compared to the misery of being bound without Love.”

Ideas about marriage were changing rapidly in Austen’s era, inspired primarily by the Romantics—poets, authors and philosophers who believed that marriage should be fueled exclusively by romantic love—but Austen also rejected this ideal.

While the Romantics insisted that choosing a partner should be about unleashing one’s most passionate feelings, Austen championed the classical, Aristotelian philosophy of balance between emotion and reason when choosing a partner for life. The successful coming of age of an Austen heroine hinges on her learning to discern the true nature of a suitor, not simply the appearance he projects. It also often requires that she look beyond her emotional impulses and fall in love with a man’s character and temperament—as in the case of Marianne Dashwood and Elizabeth Bennet, who are initially attracted to handsome, romantic rakes.

Indeed, flashy romantic suitors like Mr. Wickham and John Willoughby often prove to be wicked, scheming, and insincere. By contrast, more subdued men like Colonel Brandon and Captain Wentworth attempt to restrain their emotions in order to preserve the honor of the women they admire, and wait to betray their feelings until they are certain they are ready to propose.

Furthermore, Austen’s heroines, although driven by love, do not neglect to consider the practical implications of marrying well. After all, it is only after seeing Pemberley with her own eyes that Lizzie finally relents and accepts Mr. Darcy’s proposal, famously thinking as she looks across the valley at his vast estate: “To be mistress of Pemberley might be something!”

In all of these respects, Austen was, and still is, a fresh voice on the topic of marriage. Our own era is still firmly in the grip of the Romantic frenzy—emotional love songs, extravagant courtships and proposals, an emphasis on being swept away in one’s feelings, and fairy tales with happy endings dominate popular culture.

For Austen, a classical reverence for balance—equal parts reason and emotion—reigned supreme, especially on the part of the woman, who had far more to lose in marriage than her male counterpart. Too much reason, and you have Elinor Dashwood, a woman who is initially a little too selfless and withdrawn. Too much emotion, and you have her sister Marianne, a woman who follows her feelings straight into the arms of a charlatan. To grow, each sister must learn a little bit from the other.

As a mother of two girls, I actively seek out alternatives to what I consider an excess of focus on romance in popular culture. If my daughters choose to marry, I want them to love their future spouses with both their hearts and heads; to go into marriage clear-eyed and with reasonable expectations, and to understand that love is more than a feeling—it is also a choice and a process—and should be shared thoughtfully and carefully, with someone who is worthy of receiving it.

In this way, Austen again provides a countercultural view of love, romance and marriage; one that today’s girls and young women can take much away from.

6/ Jane Austen is a genius without peer, male or female.

The final reason that I love sharing Jane Austen with girls is that, unlike some female role models who are distinguished for being the first to do what a man did before them, Jane Austen is a genius without peer. Austen’s work, legacy, and impact on our culture are incomparable. Every day of the week, Austen fans congregate online in vast numbers, sharing their love of the author in mind-bogglingly creative and witty ways. In addition to the dozens of film, stage, and television adaptations of her novels, Jane has spurred a cottage industry of writers and makers who have dedicated their lives to celebrating her work. Austen’s face graces Britain's £10 note, she has two museums dedicated to her legacy, and the Oxford English Dictionary includes more than 1,7000 Austen citations. Jane Austen societies flourish in even the farthest reaches of the globe, putting on a dizzying number of Austen-inspired conferences, balls, parties, academic talks, book clubs, and tours each year.

To love Jane Austen is to join a sisterhood of smart, snarky, idealistic women (and men!) who embrace the joy of reveling in one of the human race’s crowning glories. In the universe of authors in the English language, only William Shakespeare—a dramatist, not a novelist—rivals Jane Austen’s astounding impact and legacy.

I’ve gleaned great happiness, inspiration, and strength from loving Jane Austen and forming friendships with Janeites around the world. I’ve introduced my own girls to Austen in the hopes that maybe someday, they will do the same.

I hope you do, too!

Enter for a chance to win a glorious Jane Austen-themed picnic basket, including a hardcover copy of A Most Clever Girl autographed by Jasmine A. Stirling!

One (1) grand prize winner receives:

A picnic basket filled with:

A copy of A Most Clever Girl: How Jane Austen Discovered Her Voice, signed by author Jasmine A. Stirling

A vintage teacup

1 oz of tea From Adagio Teas

Truffles from Moonstruck Chocolates

Gardenia hand cream

A set of Jane Austen playing cards

A $15 gift certificate to Jasmine A. Stirling’s Austenite Etsy Shop, Box Hill Goods

Two (2) winners receive:

A copy of A Most Clever Girl: How Jane Austen Discovered Her Voice, signed by author Jasmine A. Stirling

The giveaway begins March 16, 2021, at 12:01 A.M. MT, and ends April 16, 2021, at 11:59 P.M. MT.